A. Introduction

Incredibly, the significant amendments passed in 2014 to the Trade‑\marks Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. T–13 (the “Act”) and the anticipated corresponding amendments to the Trademarks Regulations (SOR/96‑195) (the “Regulations”) were still not brought into force in 2017. At present, it is believed these will be brought into force sometime in early 2019.

However, draft amendments to the Regulations were issued for comment in 2017, which provided at least some progress on the significant reforms to the Act on which we have reported in previous issues of the Annual Review.

In 2017, there have been some interesting and important decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada, Federal Court of Appeal, Federal Court, and British Columbia Court of Appeal on trademark matters, including cases involving keyword advertising, parody, injunctions, and confusion over trade dress.

B. Legislation

1. Amendments to the Trademarks Act

We reported last year that it was believed that the significant reforms to the Act passed in 2014 were likely to be brought into force in late 2018. Once again, it appears there will be further delays, and it is now anticipated that the amendments will be brought into force in 2019.

2. Amendments to the Regulations

Despite ongoing delays in the final implementation of amendments to the Act, on June 19, 2017, the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (“CIPO”) released its draft Regulations for comment.

The key changes identified in the draft Regulations include the following.

a. Term and Renewal

The new term for a trademark registration will be 10 years once the amendments to the Act come into force. The term for registrations in existence prior to the amendments coming into force will remain at 15 years until the next renewal date for the registration, at which point it will convert to the shorter 10-year term.

b. Applications

Applications for registration of trademarks will no longer include the dates of first use of the trademark by the applicant. Similarly, there will no longer be any filings of declarations of use.

Pursuant to the Madrid Protocol, international registrations of a trade‑mark through a single application by Canadians will be possible, and foreign trademark applicants will be able to include Canada in their international applications.

c. Classification System

Applicants will have to comply with the Nice Classification of goods and services, which currently applicants can do voluntarily. Existing registrations will have to be amended to include classifications within six months after a receipt of notification from CIPO and as part of the renewal process.

d. Office Actions

Similar to procedures in the United States Patent and Trademark Office, CIPO will permit third parties to raise registerability issues during the examination by CIPO of a trademark application.

e. Fees

The application filing fees and renewal fees will increase due to the classification system. The fees are detailed in the schedule to the draft Regulations.

f. Opposition and Cancellation Proceedings

The opposition proceedings in CIPO will be significantly altered. The service and filing of transcripts of cross-examinations on affidavits will be the responsibility of the party conducting the cross-examination. The service and filing of responses to undertakings given by an affiant during cross-examination on affidavits will be the responsibility of the party whose affiant is being cross-examined.

Written submissions of the parties will no longer be filed in CIPO simultaneously but rather will be in sequence. In an opposition proceeding the opponent will file first and then the applicant. However, in cancellation proceedings under s. 45 of the Act, the party requesting cancellation will file first and then the trademark registrant will file.

Copies of affidavits and statutory declarations may be filed with CIPO but the party doing so must retain the original for one year following the expiry of the applicable appeal period. Further, it appears that such evidence may be filed in CIPO electronically.

C. Administrative Practice

In 2017, CIPO issued three practice notices, which are briefly summarized below:

1. Practice in Objection Proceedings under s. 11.13 of the Act dated

September 21, 2017

With respect to objection proceedings concerning geographical indications under s. 11.13 of the Act, the practice notices entitled Practice in Trademark Opposition Proceedings, in effect since March 31, 2009, and Email Communications of Hearing Correspondence apply mutatis mutandis.

2. Correspondence Procedures dated May 10, 2017

Changes were made to the correspondence procedures with regard to:

- physical delivery of correspondence to CIPO;

- designated establishments;

- registered mail and Xpresspost;

- electronic correspondence;

- facsimile;

- online;

- electronic medium;

- general information;

- statutory holidays;

- procedures in case of unexpected office closure at CIPO; and

- procedures when CIPO is open for business but clients are unable to communicate with CIPO.

3. Email Communications of Hearing Correspondence dated March 1, 2017

Since March 1, 2017, CIPO has provided the parties to opposition or s. 45 proceedings with an email address to ensure the timely communication of incoming hearing correspondence. Parties are

requested to forward copies of all subsequent correspondence sent to the Registrar of Trademarks to the email address provided.

It is important to note that this does not provide for an additional method of correspondence with the Registrar and compliance is still required with the Regulations and practice notices with respect to opposition proceedings. Further, a list of case law will still be required to be sent five business days before the hearing.

D. Case Law

In 2017, there were a number of interesting decisions in the Supreme Court of Canada, Federal Court of Appeal, Federal Court, and British Columbia Court of Appeal on a variety of issues, including the following cases.

1. Amendment to Pleadings

The year 2017 saw a couple of interesting cases dealing with the procedural issues in trademark opposition proceedings before the Trademarks Opposition Board.

In Manufacturers Life Insurance Co. v. British American Tobacco (Brands) Ltd., 2017 FC 436, the Federal Court heard an application for judicial review of the decision in an Opposition Board proceeding where the Registrar of Trademarks (the “Registrar”) struck out a ground of opposition in the statement of opposition pleading. The opponent, Manufacturers Life Insurance Co. (“Manulife”), alleged in its statement of opposition that the amendment by the applicant, British American Tobacco (Brands) Ltd. (“BAT”), of its trademark application to rely on a different foreign registration was not in conformity with s. 30(d) of the Act.

Manulife complained that BAT would receive an advantage of an earlier entitlement date and have an impact on other parties that wanted to register a trademark in that period. Further, Manulife argued that by amending the application BAT abandoned its earlier filing date and as a result had no foreign use as set out in its amended application.

The Registrar held that the pleading in the statement of opposition did not constitute a proper ground and ordered it to be struck. Specifically, BAT had the right to amend its application under the Act to rely on a different foreign registration. The Registrar found that the allegation in the statement of opposition did not put into question BAT’s

compliance with the requirements of s. 30(d) of the Act and could not form a valid ground of opposition.

On the judicial review by the Federal Court, the issue was determined on the standard of whether the Registrar’s decision was reasonable, and the Federal Court stated that the court looks for “the existence of justification, transparency and intelligibility within the decision-making process” and considers “whether the decision falls within a range of possible, acceptable outcomes which are defensible in respect of the facts and law” (at para. 21).

The Federal Court held that the test for striking out a ground of opposition was whether “considered in the context of the law and the litigation process, the claim has no reasonable chance of succeeding” (at para. 60). In this regard, the Federal Court cited (at para. 61) the recent case of the Federal Court of Appeal in Teva Canada Ltd. v. Gilead Sciences Inc., 2016 FCA 176:

The standard of “reasonable prospect of success” is more than just assessing whether there is just a mathematical chance of success. In deciding whether an amendment has a reasonable prospect of success, its chances of success must be examined in the context of the law and the litigation process, and a realistic view must be taken.

In view of the unchallengeable right of BAT to amend its application, the Federal Court held that while Manulife’s argument was novel, it had “no reasonable prospect of success when viewed realistically in the context of the applicable law” (at para. 64).

In another case concerning an amendment of a statement of opposition, the Federal Court of Appeal in McDowell v. Automatic Princess Holdings, LLC, 2017 FCA 126 heard an appeal from the Federal Court’s dismissal of the judicial review application of the interlocutory decision of the Opposition Board’s decision to refuse to allow an amendment of the statement of opposition.

In this case, Heather McDowell (“McDowell”) opposed the application of Automatic Princess Holdings, LLC (“Automatic”) to register the trademark HONEY B. FLY. McDowell realized late in the Opposition Board proceedings that she had failed to plead confusion with her own trademarks HONEY and HONEY & Design and the provisions of s. 12(1)(d) of the Act in that regard. It was on this issue that McDowell sought to amend her statement of opposition, which was refused by the Opposition Board.

On the judicial review application brought by McDowell of this interlocutory decision of the Opposition Board, the Federal Court dismissed the application on the basis that there were no special circumstances warranting intervention of the Federal Court in the administrative proceedings before the Opposition Board. In particular, the Federal Court found that McDowell had an adequate alternative remedy to the Opposition Board’s refusal of an amendment in the form of other proceedings under the Act.

The Federal Court of Appeal in reviewing the law on this issue found that the decision of the Federal Court in Indigo Books & Music Inc. v. C. & J. Clark International Ltd., 2010 FC 859, was wrongly decided in finding that there are no special circumstances requiring judicial review where the aggrieved party could commence other proceedings, outside of the opposition proceedings, seeking a remedy such as expungement. Further, the Federal Court of Appeal held that the fact that a different proceeding, pursuant to a different statutory provision, might produce the same result does not engage the doctrine of adequate alternative remedy. The objective is to avoid fragmenting the administrative processes that already provide for a form of review. It is not to force litigants into different proceedings to obtain redress.

The Federal Court of Appeal found that the Act did not provide for administrative review of the Opposition Board’s decision to refuse the amendment and that the purpose of the amendment was to ensure that the Opposition Board considered all of the issues in its proceedings. As a result, the only form of redress was a judicial review application to the Federal Court.

Further, despite McDowell seeking the amendment more than four years after filing her statement of opposition, the Federal Court did not find this to be a determinative factor, as McDowell would not be able to split her case to the prejudice of Automatic and that Automatic could fairly respond to the new allegation in the amendment.

Consequently, the Federal Court of Appeal directed the Opposition Board to allow the amendments to the statement of opposition McDowell sought.

2. Keyword Advertising

Last year the British Columbia Court of Appeal heard an important appeal concerning confusion and keyword advertising on the Internet in Vancouver Community College v. Vancouver Career College (Burnaby) Inc., 2017 BCCA 41, leave to appeal refused 2018 CanLII 1154 (SCC).

As previously reported with respect to the lower court decision in the Annual Review for 2015, Vancouver Community College (“Community College”) commenced an action against Vancouver Career College (Burnaby) Inc. (“Career College”) for passing-off with respect to Community College’s official mark VCC. The case centred on the Career College’s use of the domain name vccollege.ca for its website and the purchase by Career College of the keyword VCC in order to promote its business online. Community College alleged that students were confused when they typed in the search term “VCC” for an Internet search and a sponsored advertisement for Career College appeared alongside the search results for websites, including Career College’s website.

At trial, Career College was successful in defending the action as the B.C. Supreme Court held that despite some evidence of actual confusion of students taking place when searching for Community College’s website using its official mark VCC as a search term, there was no passing-off found, as confusion is to be assessed at the time an ordinary consumer visited the actual websites shown on the Internet search results, and that in visiting the Career College’s website there was no use of the VCC official mark and it was clear that this was not the Community College’s website. Accordingly, the lower court found that no confusion with Career College was possible.

The Court of Appeal differed on this key finding and held that the confusion should have been assessed at the point in time when Career College’s sponsored advertisement appeared on the search results and the VCC official mark appeared as part of the domain name vccollege.ca. At this point the Court of Appeal found that a misrepresentation occurred and there was a likelihood of confusion supporting the claim of passing off.

It is important to note that the Court of Appeal held that merely purchasing competitor’s trademarks for the purpose of the keywords advertising is not in itself actionable.

While the analysis of this case is generally consistent with other cases dealing with meta-tags incorporating the trademarks of competitors, it is unfortunate that leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was refused. It would have been interesting to see the Supreme Court of Canada review the fact that it is not clear from the trial judge’s decision that Career College ever used VCC or vccollege.ca as a trademark. Normally, for an action for passing off to be successful the defendant must be shown to have used the trademark in issue as a trademark.

3. Parody and Criticism

Use of a trademark in a parody or criticism websites was thought to be given some latitude as being permissible but the decision in United Airlines Inc. v. Cooperstock, 2017 FC 616, sheds new light on this issue.

In this case, Dr. Jeremy Cooperstock (“Cooperstock”) created a website found at the domain name untied.com to post complaints and information critical of United Airlines Inc. (“United Airlines”). In addition to the use of the mark UNTIED on his website, Cooperstock added a logo to the website that resembled the globe design used by United Airlines but added a “frown” over the design. While Cooperstock made some modifications to his website in response to demands by United Airlines, he also later created a “beta” site that closely resembled United Airlines updated website. At this point, United Airlines sued Cooperstock in the Federal Court for trademark infringement, passing off, depreciation of goodwill, and copyright infringement.

Cooperstock may have felt he had support in defending his case based on two earlier cases favourably dealing with the use of trademarks to criticize corporate behaviour. However, in this instance the Federal Court took a much more friendly approach to the corporate trademark owner.

In Michelin v. Canadian Auto Workers, 1996 CanLII 11755 (FC), Michelin sued the Canadian Auto Workers union (the “Union”) for trademark and copyright infringement as well as depreciation of the goodwill of Michelins’ trademarks as a consequence of the Union using the trademark MICHELIN and Michelin’s well-known mascot on Union literature as part of an effort to unionize Michelin in Canada. With respect to the trademark infringement and depreciation of goodwill claims, the Federal Court found no trademark use by the Union as the Union did not associate its services as a union with Michelin’s trademarks and the Union did not perform any commercial activity. However, Michelin did succeed on its copyright claim as the union made a substantial copy of the Michelin mascot. Parody was not found to be a defence to this claim. It should be noted that the Copyright Act has since been amended to specifically provide for the defence of parody to infringement claims in the fair dealing provisions.

In BCAA v. Office and Professional Employees’ International Union, Local 378, 2001 BCSC 156, the British Columbia Supreme Court dealt with claims of the B.C. Automobile Association (“BCAA”) against the Office and Professional Employees’ International Union. In this case,

the union registered the domain names bccaonstrike.com and bcaabacktowork.ca and operated websites critical of BCAA. Further, the union used variations of these domain names as mega-tags in furtherance of its strike action against BCAA. Prior to the trial of the action, the union removed the BCAA name from its websites. The court held that use of the additional words “on strike” and “back to work” were sufficient to show a lack of commercial activity and that it would be readily apparent that the union’s website was not associated with BCAA, in particular as there was a disclaimer to identify that the union was on strike against BCAA. In this case, the court again found copyright infringement.

However, in the recent situation of Cooperstock’s parody website criticizing United Airlines, the Federal Court took a very different approach. On the facts of this case, the Federal Court found that the parties were operating in an identical market and provided similar services in that both Cooperstock’s website and that of United Airlines provided for pre-flight information and post-flight complaints to be posted. Further, Cooperstock admitted he wanted to maximize the resemblance to United Airline’s website and in doing so he took the substantial part or the entirety of the United Airlines trademarks and only made small changes. As well, there was some evidence of actual confusion: a travel agent mistakenly believed she was making a complaint to United Airlines in using Cooperstock’s website. On this basis, the Federal Court found against Cooperstock for passing off.

Further, the Federal Court found the Cooperstock had depreciated the goodwill of United Airlines’ trademarks. In this regard, the Federal Court did find there was trademark use within the meaning of the Act as Cooperstock’s stated intention was to identify United Airlines as the object of his criticism. The use was disparaging of United Airlines through the depiction of such things as a “frown” over United Airlines globe design.

Interestingly, in finding that the parties both operated in the same channel of trade, the Federal Court clearly downplayed the obvious intent of Cooperstock to operate a criticism website and the effect of the disclaimer posted stating, “This is not the website of United Airlines”. As Cooperstock himself said, “you’d have to be somebody who is, you know, cognitively challenged … to believe that they’re actually complaining to the airline” through his website.

It should also be noted that the Federal Court also found that Cooperstock infringed the copyright of United Airlines despite the amendments to the Copyright Act to allow for parody in the fair

dealing exception. While the Federal Court found Cooperstock’s website to be “parody” within the meaning of the Copyright Act, it was found to be not “fair”, as it was not humourous and was intended simply to defame or punish United Airlines.

It will be important to watch the effect of this decision as it may have a chilling effect on complaint websites. Many businesses have a customer care aspect to their websites and the Federal Court’s analysis of trademark use in this context creates opportunities for corporate trademark owners seeking to use trademark law to shut down criticism or parody websites.

4. Injunctions

Interlocutory injunctions in trademark matters have historically been difficult to obtain in the Federal Court since at least the mid-1990s. However, the case of Sleep Country Canada Inc. v. Sears Canada Inc., 2017 FC 148, has raised the notion that the Federal Court may be altering this situation and will be more willing to grant interlocutory injunctions in the future.

Sleep Country Canada Inc. (“Sleep Country”) commenced a trademark infringement action against Sears Canada Inc. (“Sears”) over Sears’ use of the slogan “there is no reason to buy a mattress anywhere else”, which Sleep Country alleged was confusingly similar to its registered trademark slogan “why buy a mattress anywhere else?”, which had been used since 1994. In doing so, Sleep Country sought an interlocutory injunction against Sears.

The test for granting an interlocutory injunction is as follows:

(1) whether a serious issue has been raised;

(2) whether the applicant suffer irreparable harm if the injunction is not granted; and

(3) whether the balance of convenience favours the applicant.

Interlocutory injunction applications often fail on the second part of test as to whether the plaintiff will suffer irreparable harm. This part of the test cannot generally be satisfied if the harm suffered by the plaintiff could be compensated for in monetary damages. The case law on this issue has added the gloss that the evidence of irreparable harm must be “clear and non-speculative” (see Centre Ice Ltd. v. National Hockey League (1994), 53 C.P.R. (3d) 34 (FC)).

This “clear evidence” of irreparable harm has been typically found where the alleged infringer had not yet entered the market or where

the plaintiff was attempting to stop an alleged infringer from being “first to market” so as to make it impossible to quantify damages suffered.

However, on the facts of this case, such circumstances were not in play. Despite this, Sleep Country was successful in obtaining an injunction from the Federal Court.

Sleep Country was successful by establishing irreparable harm through the “clear evidence” of the expert evidence it provided to the Federal Court. Specifically, Sleep Country provided evidence from a professor of marketing and chartered professional accountant. These experts opined that the harm attributable to Sears’ alleged infringement was not quantifiable monetarily and stated that isolating the impact of the use of Sears’ new slogan from market forces to do so was impossible.

As well, the Federal Court was not convinced by the evidence of Sears’ expert in attacking the experts of Sleep Country. Importantly, the Federal Court found that Sears’ expert failed to comply with the Code of Conduct for experts under the Federal Court Rules.

This case shows that an interlocutory injunction may be more readily granted if the evidence of experts is clear and non-speculative in supporting that the harm suffered cannot be compensated for in monetary damages. However, it is important to note that the marks in issue were nearly identical; the reasons proffered for use of the alleged infringing marks by Sears were not seen as credible by the Federal Court; Sleep Country had used its mark for 22 years prior to Sears; and the expert evidence provided to the Federal Court by Sears that the harm to Sleep Country could be compensated in damages was flawed.

Ultimately, the significance of this case may be that proving irreparable harm is a complex matter of expert evidence. While this case created some excitement over whether interlocutory injunctions are now easier to obtain, it may be that this is not the case because a very high standard of evidence is still required.

In a very significant case in 2017, also relating to injunctions, the Supreme Court of Canada heard the appeal in Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc., 2017 SCC 34 from the decision of the British Columbia Court of Appeal.

The case had its origins as an action by Equustek Solutions Inc. (“Equustek”) against Datalink Technology Gateways Inc., Datalink Technologies Gateways LLC, and their principal, Morgan Jack

(collectively “Datalink”), for trademark infringement and appropriation of trade secrets. Initially, Datalink was located in British Columbia but after filing its Statement of Defense, Datalink continued to fulfil online orders on its website to customers all over the world for the infringing products from locations unknown to Equustek. Datalink did so despite an injunction order that Datalink cease carrying on business through any website.

In response to ongoing sales of infringing products, Equustek asked Google Inc. (“Google”) to de-index Datalink websites. Google did so with respect to specific webpages and Google’s Canadian domain only. As a result, Datalink simply moved the infringing material to new pages and on other domains such as google.com.

In frustration, Equustek obtained an interlocutory injunction to enjoin Google from displaying any part of Datalink’s websites on any of its search results worldwide. The British Columbia Court of Appeal dismissed Google’s appeal of this injunction order. Google then appealed the injunction order to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The case is important as the far-reaching injunction order was one that purported to give Canadian courts the power to grant injunctions with extraterritorial effect.

The Supreme Court was clear that the courts can order injunctive relief against someone who is not a party to the underlying lawsuit, such as Google. The injunction in this case was required to prevent Datalink from defying court orders. Without the injunction, Google would be continuing to facilitate the ongoing harm.

Further, to ensure the effectiveness of an injunction, the Supreme Court held that a Canadian court can do so on a worldwide basis. As the problem was happening online over the Internet, it was a global problem. Restricting the remedy to Canada alone or google.ca deprived the remedy of its intended ability to prevent irreparable harm.

The Supreme Court dismissed Google’s arguments that such a wide-ranging order violated the principle of international comity because such an order may put Google in breach of foreign laws. It did so on the basis that if the injunction did require Google to violate laws of another jurisdiction, including interfering with freedom of expression, Google was free to apply to the B.C. courts to vary the order accordingly.

It is noteworthy that two justices of the Supreme Court dissented from the majority view on a number of grounds. Firstly, the interlocutory order against Google had the effect of a final determination, as there was no incentive for Equustek to pursue the legal proceedings any further. This was evidenced by Equustek’s failure over five years to obtain default judgment despite being entitled to do so. The test for an interlocutory injunction order does not apply to that of a permanent injunction, and it was not established that Datalink infringed Equustek’s trademark or unlawfully appropriated trade secrets. Further, Google was a non-party to the legal proceedings between Equustek and Datalink, and the minority view was that Google was not aiding or abetting the prohibited acts of Datalink. As well, the minority view noted that the injunction obtained was an onerous mandatory one requiring an on-going modification and supervision, and Canadian courts should avoid granting such injunctions. Significantly, the dissenting justices pointed out that the injunction against Google was not shown to be effective in making Datalink cease carrying on business through any website. Datalink’s websites could be found on other search engines. Finally, the dissenting justices pointed out that Equustek potentially had other remedies at its deposal such as pursuing its efforts to freeze Datalink’s assets in France.

It remains to be seen if the dissenting justices’ points will have relevance in the development of this powerful new tool for Canadian courts.

However, what is clear is that the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision opens up new possibilities for intellectual property owners to enforce their rights in a wide-ranging fashion when the infringing matters are carried out over the Internet and on a global basis.

5. Confusion

Disputes among liquor companies were featured once again in 2017 in Diageo Canada Inc. v. Heaven Hill Distilleries, Inc., 2017 FC 571, where it was a battle between Captain Morgan rum and Admiral Nelson rum in which the Captain defeated the Admiral.

Diageo Canada Inc. (“Diageo”) is part of a large international liquor manufacturing and distribution group owning many well-known brands, including Captain Morgan for its rum products. Diageo has numerous trademark registrations for its Captain Morgan rum, including many registrations for the depiction on the labels of the Captain Morgan character, which has evolved and varied over time.

Heaven Hill Distilleries, Inc. (“Heaven Hill”) is a large United States manufacturer and supplier, which sold Admiral Nelson rum in Canada with a depiction of the famous admiral on the labels of its products.

The dispute between Diageo and Heaven Hill centred on the trade‑dress or “get-up” of the respective rum products and the related trade‑mark registrations of Diageo for its Captain Morgan character rather than the word marks ADMIRAL NELSON and CAPTAIN MORGAN. The principal rum products in dispute were as follows:

Specifically, Diageo claimed passing off, trademark infringement, and depreciation of goodwill with respect to Heaven Hill’s Admiral Nelson rum product trade dress.

Interestingly, in response, Heaven Hill alleged, among other things, that a number of trademark registrations relied on by Diageo depicting the Captain Morgan character were invalid because Diageo had abandoned their use. While these trademarks were not used by Diageo for many years and Diageo had no present intention to relaunch products bearing the trademarks, this ground of attack failed as there was no intention of Diageo’s part to actually abandon their trademark registrations or allow the registrations lapse. Further, the court noted that Diageo’s alleged abandoned trademarks were “associated marks” with Diageo’s later registrations currently in use. The question in this regard was whether the trademarks Heaven Hill alleged as abandoned were substantially different from the subsequent trademark registrations such that the later depictions in use were not mere variants of the earlier registered trademarks alleged to be abandoned. The court was satisfied that despite differences of the later depictions of Captain Morgan having a raised leg on a barrel and different clothing and attire, the depictions mostly had the same elements of a strap across the chest, an ascot, a sword in the right hand,

a cape, a prominent moustache and long dark hair, a nearly knee‑length naval jacket or coat with exaggerated cuffs, and a fanciful hat. All of these similarities were sufficient to show these “associated marks” were not substantially different and therefore not abandoned.

With respect to overall design of the unregistered trade dress of the bottle and label of the Captain Morgan and Admiral Nelson products, the court agreed with Diageo that the Heaven Hill design created “an illusion of sameness”. The court dismissed Heaven Hill’s argument that there could be no passing off as there were a number of other rum products sold in Canada that used nautical or British naval themes such as sailing ships, naval officers, and even some with pirate characters. The court further dismissed Heaven Hill’s argument that there were substantial differences between the Captain Morgan and Admiral Nelson trade dress, which Heaven Hill cited as the use of the words ADMIRAL NELSON in vertical stacked form, the depiction of the Captain Morgan character with one leg up on a barrel while the Admiral Nelson character had two feet on the ground and a tankard in one hand, different background elements, and different colours used.

It appears that the court was persuaded in finding a likelihood of confusion between the parties respective products on the basis of the expert report of a consumer survey that assessed the general impressions of Admiral Nelson rum and the extent to which purchasers mistakenly inferred that this product originated from the same source as Captain Morgan rum. Diageo’s expert evidence claimed that “one can conclude with 95% confidence that the inference of a same source between these two bottles, Admiral Nelson and Captain Morgan, arises from some elements on the Admiral Nelson’s bottle … ” (at para. 87) and that 23% of the survey participants had a misapprehension as to the source of the products. After reviewing the critique of Diageo’s experts’ evidence, the court was satisfied that the percentage of people interviewed in the survey that were confused as to the source of the Admiral Nelson product was somewhere between 11 and 28%. The court noted that the rate of confusion previously found to be sufficient to establish a likelihood of confusion in the case law ranged from as little as 4.8 to 8.2% in one case and 11 to 13.5% in others.

As a result, the court made a determination of passing off and trade‑mark infringement against Heaven Hill. Following its other findings, the court also found that the Admiral Nelson products depreciated the goodwill of the Captain Morgan product, as it noted that there were quality control issues concerning some of the Admiral Nelson products.

The Federal Court of Appeal in U-Haul International Inc. v. U Box It Inc., 2017 FCA 170, upheld the decision of the Opposition Board and the Federal Court to reject the trademark application of U-Haul International Inc. (“U-Haul”) for its trademarks U-BOX and U-BOX WE HAUL (the “U-Haul Marks”). The U-Haul Marks were used in association with moving and storage services, namely, rental, moving and storage, and delivery and pick up of portable storage units.

U-Haul was opposed by U Box It Inc. (“UBI”) in the Opposition Board proceedings based on UBI’s assertion that the U-Haul Marks were confusing with its registered trademark that UBI used in association with garbage removal and waste management services (the “UBI Mark”).

The Federal Court of Appeal took no issue with the Federal Court’s review of the Opposition Board’s decision on the basis of whether it was a reasonable decision as opposed to undertaking a de novo review of the matter. Further, it took no issue with the lower court’s support of the decision of the Opposition Board that there was a likelihood of confusion between the U-Haul Marks and the UBI Mark. The Federal Court of Appeal stated that the Opposition Board’s decision was within a range of reasonable outcomes and quoted the Supreme Court of Canada that the “determination of the likelihood of confusion requires an expertise that is possessed by the Board (which performs such assessments day in and day out) in greater measure than is typical of judges … ” (See Mattel Inc. v. 3894207 Canada Inc., 2006 SCC 22 at para. 36).

In particular, the Federal Court of Appeal did not find any error with respect to the finding of the Opposition Board that the channels of trade of the parties were not so different as to avoid the likelihood of confusion, although this was difficult to reconcile with the Opposition Board’s conclusion that this factor did not favour either party. The Federal Court of Appeal noted UBI’s garbage removal business is performed in a similar fashion to U-Haul’s business, whereby a large box is supplied to a customer and, after being filled with waste by the customer, the box is picked up for disposal.

Accordingly, the appeal of U-Haul was dismissed.

In Benjamin Moore & Co. Ltd. v. Home Hardware Stores Ltd., 2017 FCA 53, the Federal Court of Appeal granted an appeal from the Federal Court in a matter concerning the material dates to be used when assessing whether there is confusion between a family of trademarks and another trademark.

Home Hardware Stores Ltd. (“Home Hardware”) opposed the application for registration by Benjamin Moore & Co. Ltd. (“Benjamin Moore”) of its trademarks BENJAMIN MOORE NATURA and BENJAMIN MOORE NATURA & Design used in association with interior and exterior paints (the “Benjamin Moore Marks”). Home Hardware opposed on the basis that the Benjamin Moore Marks were confusing with Home Hardware’s NUTRA family of trademarks unrelated to paint and its unregistered BEAUTI-TONE NATURA trademark used in association with paints. The Opposition Board rejected Home Hardware’s opposition to registration finding that the parties’ respective marks were not confusing at any of the material dates.

On appeal by Home Hardware to the Federal Court, the matter was reviewed on a de novo basis. The Federal Court overturned the Opposition Board’s decision and found that there was a likelihood of confusion between the Home Hardware NUTRA family of trademarks, particularly the unregistered BEAUTI-TONE NATURA trademark used in association with paints.

In response, Benjamin Moore appealed this decision to the Federal Court of Appeal on the basis that the Federal Court erred in law in failing to apply the “mark to mark” comparative analysis when assessing confusion between the Home Hardware family of marks and the Benjamin Moore Marks and the Federal Court failed to consider the relevant material dates for each ground of opposition. Home Hardware argued that a “mark to mark” comparative analysis was not necessary where it had built up a family of marks. However, the Federal Court of Appeal agreed with Benjamin Moore and held that while a family of marks is relevant in assessing confusion, the “use of a family of marks does not obviate the need to undertake a full comparative confusion analysis on a mark to mark basis for each relevant ground of opposition” (at para. 32). The Federal Court of Appeal also held that the lower court erred in its confusion analysis by not limiting its consideration to the earliest material date with respect to the trademarks used in association with paint.

As a result of the errors of the Federal Court in applying the wrong material date for determining that the paint trademarks were confusing, the Federal Court of Appeal allowed the appeal and referred the matter back to the Federal Court for a redetermination.

In Stork Market Inc. v. 1736735 Ontario Inc., 2017 FC 779, it was a battle of lawn sign companies over the use of stork images as trade‑marks.

Stork Market Inc. (“SMI”) and 1736735 Ontario Inc. (“173 Ontario”) both operated in the Greater Toronto Area and parts of Southern Ontario and both rented lawn signs intended to celebrate special occasions such as the announcement of the birth of a child.

SMI used a stork image on its lawn signs, which were registered as follows:

(the “SMI Marks”).

173 Ontario also used a stork image on its lawn signs as follows:

(the “173 Ontario Marks”).

SMI commenced an action against 173 Ontario for trademark infringement and passing off. In response, 173 Ontario counterclaimed that the SMI Marks were not valid trademark registrations and should be expunged on the basis that the SMI Marks were not distinctive of a

single source and that the subject matter of the SMI Marks were primarily functional and/or merely ornamental.

The Federal Court dismissed the counterclaims. With respect to the distinctiveness issue, the Federal Court agreed that there was no evidence at trial as to a written or express license between SMI and the principal and sole employee of SMI, who actually registered the SMI Marks in his personal name. However, this did not lead to a finding of a lack of distinctiveness in the SMI Marks as the Federal Court noted that the required license could be an oral license inferred where the owner exercises control over the use of the trademarks. The Federal Court was prepared to do so in the circumstances of this case.

With respect to the functional or ornamental issue, the Federal Court reviewed the law prohibiting such marks. Specifically, it quoted the Supreme Court of Canada in Kirkbi AG v. Ritvik Holdings Inc., 2005 SCC 65 at para. 42, as follows:

The doctrine of functionality appears to be a logical principle of trademarks law. It reflects the purpose of a trademark, which is protection of the distinctiveness of the product, not a monopoly on the product.

In short, the Federal Court recognized that the Act does not protect the utilitarian features of a trademark and a trademark is intended to identify the source of a product. If a trademark is primarily functional, it is invalid.

173 Ontario argued that the SMI Marks were primarily functional on the basis that if the stork image is removed, the goods would no longer function as “lawn storks” and the services would no longer function as “rental services of the stork image on a wooden plank”,

While the Federal Court acknowledged that the images for which SMI claimed trademark protection are themselves an integral part of SMI’s product and services, 173 Ontario did not cite any authority to support a conclusion that this in itself disentitles SMI to such protection. The Federal Court found that there was no authority that a product cannot have features that serve a utilitarian function but also serve the trademark function of identifying the source of the product without necessarily invalidating the trademark registration.

In support of this finding on the facts of the case, the Federal Court identified the use of the stork images as branding on, among other things, SMI’s website, promotional materials, business cards, posters, and decals on the sides of a vehicle.

Having dismissed the counterclaims of 173 Ontario, the Federal Court then turned to SMI’s allegations of trademark infringement and passing off. In this regard, the Federal Court found there was a likelihood of confusion supporting infringement and passing off in favour of SMI. In assessing the key factor of the degree of resemblance between the SMI Marks and the 173 Ontario Marks, the Federal Court was persuaded that there were unique or particularly striking aspects shared by the respective marks. Specifically, these were found to be the overall configuration and pose of the stork, facing forward with splayed legs, raised feathered wings, and banner above its head.

Accordingly, the Federal Court enjoined 173 Ontario from further use of the 173 Ontario Marks and awarded damages against 173 Ontario in the sum of $30,000 based on the evidence tendered by SMI.

6. Distinctiveness

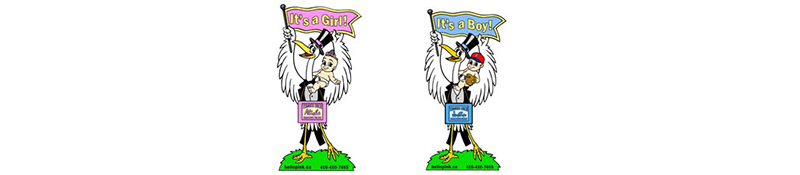

Last year we reported on an interesting case concerning the distinctiveness of trademarks in an infringement and passing-off action in Wenger S.A. v. Travelway Group International Ltd., 2016 FC 347. This case was appealed to the Federal Court of Appeal in Group III International Ltd. v. Travelway Group International Ltd., 2017 FCA 215. Wenger S.A. (“Wenger”), the maker of the famous Swiss army knives, disputed the finding of the Federal Court that the marks used by Travelway Group International Ltd. (“Travelway”) were not confusing with Wenger’s trademarks, in part because Wenger’s trademarks had not acquired distinctiveness such that they had become known to consumers as originating from one particular source, Wenger. The following Wenger trademarks in issue were registered in association with, among other things, luggage and bags (the “Wenger Marks”):

Similarly, the following Travelway marks were used in association with travel related products (the “Travelway Marks”):

The Federal Court of Appeal agreed with Wenger finding that the lower court failed to review all of the criteria for confusion under s. 6(5) of the Act other than the degree of resemblance factor.

In its analysis of the factors found in s. 6(5) of the Act in determining whether a likelihood of confusion exists, the Federal Court found that the Wenger Marks and the Travelway Marks bore a “very strong resemblance” to each other, but also that the other factors such as the length of time each mark was in use and their inherent distinctiveness favoured in finding a confusion. In this regard, while neither the Wenger Marks nor Travelway Marks were inherently distinctive, the Wenger Marks had acquired distinctiveness as a result of many years of strong sales in Canada, with use commencing approximately six years before Travelway. Further, the Federal Court of Appeal found that the existence of third party “Swiss cross” marks would “not completely erode the acquired distinctiveness of the Wenger cross mark that it has gained through the years of strong sales” (at para. 55).

As a result, the Federal Court of Appeal found in favour of Wenger with respect to its trademark infringement and passing-off claims.

7. Section 22—Depreciation of Goodwill

In Venngo Inc. v. Concierge Connection Inc., 2017 FCA 96, leave to appeal refused 2017 CanLII 78708 (SCC), the Federal Court of Appeal heard an appeal from the Federal Court in an action brought by Venngo Inc. (“Venngo”) against Concierge Connection Inc. (“CCI”) for trademark infringement, passing off, and depreciation of goodwill under the Act.

Venngo was the owner of a family of registered trademarks using the suffix PERKS, including WORKPERKS, MEMBERPERKS, ADPERKS, PARTNERPERKS, CLIENTPERKS, and CUSTOMERPERKS (the “Venngo Marks”), in association with a broad category of goods and services. Venngo took issue with CCI’s PERKOPOLIS mark in which it registered in association with entertainment ticket sales and hotel booking services. However, CCI actually used the WORKOPOLIS mark for a variety of goods and services beyond those identified in its registration.

At trial, the Federal Court found in favour of CCI determining there was no likelihood of confusion leading to trademark infringement or passing off based on the factors cited in s. 6(5) of the Act. The trial judge found that the Venngo Marks lacked inherent distinctiveness as they were highly suggestive, if not descriptive, such that they only deserved a narrow ambit of protection. Further, the trial judge found that there was little resemblance between CCI’s PERKOPOLIS Mark and the Venngo Marks in appearance, sound, or the ideas suggested by them.

With respect to the claim for depreciation of goodwill under s. 22 of the Act, the trial judge stated that “[u]se under s. 22 requires use of a plaintiff’s trademark, as registered” and rejected this claim as well.

The Federal Court of Appeal dismissed Venngo’s appeal and upheld the trial judge’s decision. In doing so, it is noteworthy that the Federal Court of Appeal agreed with Venngo that the trial judge’s statement with respect to s. 22 of the Act was an error as it is not necessary for the plaintiff Venngo to show in its claim for depreciation of goodwill use by CCI of its identical trademark. The Federal Court of Appeal determined that any such error by the lower court was irrelevant to the appeal, as it found that the Federal Court did not reject Venngo’s claim for depreciation of goodwill on this basis but rather because CCI’s impunged use of the words MEMBER PERKS INCLUDE on two of CCI’s websites did not constitute use of a trademark within the meaning of s. 22 of the Act.

8. Personal Liability and Damages

In 2017, Annie Pui Kwan Lam (“Lam”) once again appealed the significant personal liability damage award against her to the Federal Court of Appeal. As reported last year, the Federal Court of Appeal remitted back to the Federal Court trial judge to review the damages awarded against Lam for the sale of counterfeit goods of Channel S. de R.L. (“Chanel”): $64,000 in compensatory damages and $250,000

in punitive damages. On review by the lower court, these damages were confirmed with more detailed reasons and analysis of the evidence. It is this review by the lower court that was once again appealed to the Federal Court in 2017, in Lam v. Chanel S. de R.L., 2017 FCA 38.

In reviewing the damage award of the trial judge for a second time, the Federal Court of Appeal was satisfied with the more detailed reasoning and the analysis of the supporting evidence provided by the Federal Court.

The Federal Court of Appeal rejected Lam’s argument that the punitive damages should be calculated based on a ratio of the compensatory damages awarded. Further, in its decision, the Federal Court of Appeal noted key findings of the trial judge as follows (at para. 11):

… the defendants were motivated by profit; the vulnerability to, and erosion of, the plaintiff’s trademark rights arising from counterfeiting and infringement; the defendants’ attempt to mislead the court; the fraudulent transfer, after the filing of the Statement of Claim, of ownership of the defendants’ company to avoid liability; the defendants’ recidivist conduct in light of previous orders in respect of the same matter; the defendants’ awareness of the unlawful nature of the activity; the scope of the infringement; the sale of infringing articles after filing and service of the Statement of Claim; the defendants’ failure to produce any records; and, the judge’s conclusion that the infringement was continuous and deliberate.

These key findings are undoubtedly a road map to higher than usual damage awards.

9. Section 45

In Estee Lauder Cosmetics Ltd. v. Loveless, 2017 FC 927, the Federal Court heard an appeal from a decision of the Registrar of Trademarks under s. 45 of the Act that dealt with the issue of whether delivery of samples to a purchaser bearing a trademark is use of that trademark within the meaning of the Act.

Under s. 45 of the Act, registered trademarks that have not been used for three years prior to the date of notification under this provision are struck from the trademark register following the policy that trademarks are only valid if used. Use under s. 4 of the Act is established if, “at the time of the transfer of property in or possession of the goods, in the normal course of trade”, the trademark is marked on the goods

or package or in a manner so associated with the goods, notice is given of use of the trademark.

In this case, at the request of Sharlene Loveless (“Loveless”) the Registrar issued a notification under s. 45 of the Act with respect to Estee Lauder’s registered trademark ENLIGHTEN used in association with face makeup. In response, Estee Lauder submitted an affidavit indicating that the company had entered into agreements with Canadian retailers to ship to them its goods bearing the ENLIGHTEN trademark during the relevant three-year period. However, the Registrar struck Estee Lauder’s ENLIGHTEN trademark from the register as there was no evidence that the orders for the goods had been confirmed by the purchasing retailers.

Estee Lauder appealed this decision to the Federal Court. In doing so, Estee Lauder submitted new evidence that the orders for the goods it relied on to show use of the ENLIGHTEN trademark were confirmed by the purchasing retailers during the relevant period and that such goods had been “sampled” by such purchasers during the relevant period.

In its review of the Registrar’s decision, the Federal Court held that the new evidence did constitute agreements to purchase goods bearing the ENLIGHTEN trademark and that they were both substantial and confirmed within the relevant period. However, the Federal Court found that this in itself was still insufficient to show use within the meaning of s. 45 of the Act. In the view of the Federal Court, this was not sufficient to show that property in such goods had been “transferred” within the relevant period.

However, the Federal Court then turned to the issue of whether providing samples bearing the ENLIGHTEN trademark to retailers during the relevant period constituted “transfer of property or possession in the normal course of trade” so as to constitute use under the Act.

The Federal Court held that while free delivery of samples bearing a trademark do not meet the requirement for use under s. 4 of the Act, if there are subsequent sales of the samples this will be seen as part of the sale in the normal course of trade and satisfy the requirement for use under s. 4 of the Act.

On the facts of this case, the Federal Court found that Estee Lauder’s samples of the ENLIGHTEN trademarked goods during the relevant period were for the purpose of securing orders for these goods and that Estee Lauder ultimately secured those orders, albeit after the relevant

period. In the view of the Federal Court, this constituted a transfer of property or possession within the normal course of trade and therefore “use” during the relevant period of the trademark within the meaning of the Act.

Accordingly, the Federal Court granted Estee Lauder’s appeal and the decision to strike the ENLIGHTEN trademark from the register was set aside.

10. Split Decisions

In Metro Brands S.E.N.C. v. 1161396 Ontario Inc., 2017 FC 806, the Federal Court clarified whether the Registrar of Trademarks has the jurisdiction to issue a “split” decision pursuant to the s. 38(8) of the Act.

In this case Les Marques Metro/Metro Brands S.E.N.C. (“Metro”) opposed the application for registration by 1161396 Ontario Inc. (“116 Ontario”) of the mark IRRESISTIBLES in association with “candy and snacks, namely candy bars, chocolate bars, all sugar confectionary, peanut brittle, caramel bars, cookies & biscuits, all gummi confectionary, chocolate confectionary, chocolate mints, assorted chocolate boxes and marshmallow derivative candy” (the “Irresistibles Mark”).

Metro opposed the Irresistibles Mark on the grounds that it was not used by 116 Ontario in association with the specific goods of “cookies and biscuits” at the claimed date of first use. The Opposition Board rejected Metro’s ground of opposition as Metro failed to discharge its initial evidentiary onus and accordingly dismissed the opposition.

In response, Metro appealed to the Federal Court and filed new evidence in support of its position that 116 Ontario had not used the Irresistibles Mark as of the first use date claimed.

The Federal Court made clear that 116 Ontario must have used the Irresistibles Mark in association with all of the goods listed in 116 Ontario’s application, including “cookies & biscuits”, as of the first use date claimed, if the trademark application was to be allowed.

On the facts the Federal Court found that the new evidence on appeal by Metro was sufficient to discharge the initial evidentiary onus on it to show that 116 Ontario did not use the Irresistibles Mark in association with “cookies & biscuits” as of the first use date claimed. Since 116 Ontario had not provided any evidence at the Opposition Board stage on this issue and none on the appeal, 116 Ontario was not

able to rebut this evidence. Accordingly, the Federal Court granted Metro’s appeal on this point.

However, this still left a dispute about whether the Opposition Board could still allow 116 Ontario’s application by effectively deleting the goods “cookies & biscuits” from the application or whether it must reject the whole application.

In this regard, the Federal Court noted s. 38(8) of the Act states that the “Registrar shall refuse the application or reject the opposition”, which does not appear to expressly grant the Opposition Board jurisdiction to allow oppositions to only succeed in connection with some goods or services. Further, the Federal Court noted that the decision in Coronet-Werke Heinrich Schlerf GmbH v. Produits Ménagers Coronet Inc. (1986), 10 C.P.R. (3d) 482 (FCTD), usually cited in support of split decisions for over 30 years in Opposition Board cases, did not provide a textual, contextural, or purposive analysis of s. 38(8) of the Act in support of the jurisdiction to issue split decisions.

However, the Federal Court found that as a matter of policy, and as an object of the Act, s. 38(8) should be interpreted as providing for the issuance of split decisions. To do otherwise, would have the “perverse effect of encouraging inefficient practices”. The Federal Court stated this would encourage applicants to file multiple trademark applications instead of a single one to avoid the risk of an active trademark application being refused due to a single good or service listed being unregisterable. This would in turn lead to higher costs for applicants and multiply the number of oppositions. Accordingly, the Federal Court was prepared to uphold the generally accepted practice in Opposition Board proceedings to render split decisions. It is noteworthy that the proposed amendments to the Act if in force now would have avoided this dispute, as first use dates will no longer be required in trademark applications and split decisions would be expressly recognized under the Act.