On December 15, 2009, the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal from a trial court’s decision that upheld the 2003 Nova Scotia legislation which caps damages for pain and suffering resulting from “minor injuries” at $2,500. Just two days later, on December 17, 2009, the Supreme Court of Canada denied leave to appeal the decision of the Alberta Court of Appeal which upheld similar legislation. As a result, unless an appellate court in another Canadian jurisdiction strikes down such legislation, it is unlikely that the Supreme Court of Canada will hear a case on the constitutionality of a legislated cap on damages for pain and suffering.

It will be interesting to see whether other provinces follow suit and enact this kind of legislation, especially now that its enforceability seems almost certain. As it stands, only Alberta, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick have such legislation in place. However, the cited impetus for the legislation is a concern that plagues virtually ever province across Canada: the rising costs of insurance. In the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal’s decision, the Court noted that the Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board had identified significant increases in third party liability claim costs as a major contributor to rising insurance premiums. In response, a Nova Scotia minority Conservative government introduced new provisions into the existing Insurance Act and regulations, limiting damages for pain and suffering stemming from “minor injury” to $2,500.

The Alberta legislation, which dates back to 2004 and caps damages for pain and suffering for “minor injury” at $4,000, was introduced for similar reasons. In its decision, the Alberta Court of Appeal noted that the minor injury legislation was the Government of Alberta’s response to concerns about rising insurance premiums, which were tied, in part, to rising claims costs. The Court cited a report that found that “by 2006, the percentage of non-pecuniary damage settlements had increased to over 70 percent of settlement amounts. Sixty two percent of claims were for soft tissue strains or sprains, and these claims accounted for 43 percent of total settlement amounts”.

The legislation does appear to have significant benefits: the Alberta Court of Appeal noted in its decision that after the minor injury legislation was introduced, premiums fell by 18% (albeit because of mandated reductions). But as can be expected, the legislation has plenty of critics, many of whom point to the fact that the legislation determines a claimant’s entitlement to damages solely on the basis of the type of injury suffered, rather than on the impact on the particular individual. It has been argued (unsuccessfully, in both the Alberta and Nova Scotia Courts of Appeal) that this treatment results in a breach of the rights protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, in particular, section 15 which guarantees the right to equal treatment and benefit under the law.

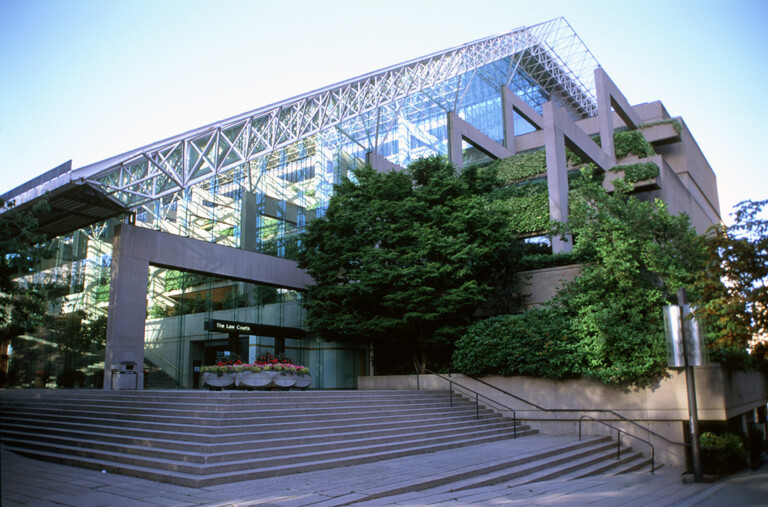

Thus far, there does not appear to be any plans on the part of the BC Government to introduce this kind of legislation. There is much still to learn about the practicality of the cap legislation, in particular, whether it will be interpreted by Courts applying it in such a way that actually results in a meaningful impact on damage awards. If the thrust of the legislation is ultimately undermined by judicial interpretation, then it may prove not to be as useful a tool as insurers might have hoped.